monmec

is marius parghel

verifica asta afara VIII

Kodachrome is a brand name for a non-substantive, color reversal film introduced by Eastman Kodak in 1935.It was one of the first successful color materials and was used for both cinematography and still photography. Because of its complex processing requirements, the film was sold process-paid in the United States until 1954 when a legal ruling prohibited this. Elsewhere, this arrangement continued. For many years it was used for professional color photography, especially for images intended for publication in print media. Because of the uptake of alternative photographic materials, its complex processing requirements, and the widespread transition to digital photography, Kodachrome lost its market share, its manufacturing was discontinued in 2009 and its processing ended in December 2010.

Kodachrome was the first color film that used a subtractive color method to be successfully mass-marketed. Previous materials, such as Autochrome and Dufaycolor, had used the additive screenplate methods. Until its discontinuation, Kodachrome was the oldest surviving brand of color film. It was manufactured for 74 years in various formats to suit still and motion picture cameras, including 8 mm, Super 8, 16 mm for movies (exclusively through Eastman Kodak), and 35 mm for movies (exclusively through Technicolor Corp as “Technicolor Monopack”) and 35 mm, 120, 110, 126, 828 and large format for still photography.

Kodachrome is appreciated in the archival and professional market for its dark-storage longevity. Because of these qualities, it was used by professional photographers like Steve McCurry, Peter Guttman[3] and Alex Webb. McCurry used Kodachrome for his well-known 1984 portrait of Sharbat Gula, the “Afghan Girl” for the National Geographic magazine.[4] It was used by Walton Sound and Film Services in the UK in 1953 for the official 16 mm film of the coronation of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Copies of the film for sale to the public were also produced using Kodachrome.

———————————————-

The first, commercially unsuccessful, Kodak product called Kodachrome was invented by John Capstaff, a former portrait photographer and physics and engineering student.

The next version of Kodachrome was invented in the early 1930s by two professional musicians, Leopold Godowsky, Jr. and Leopold Mannes,who were also university-trained scientists.

—————————

Their experiments, which continued after they finished college, turned from multiple lenses that produce multiple, differently coloured images that had to be combined to form the final transparency, to multiple layered film in which the different colour images were already combined, perfectly aligned. Such a multi-layered film had already been invented and patented in 1912 by the German inventor Rudolph Fischer. Each of the three layers in the proposed film would be sensitive to one of the three primary colours, and each of the three layers would have substances (called “colour couplers”) embedded in them that would form a dye of the required colour when combined with the by-products of the developing silver image. When the silver images are bleached away, the three colour dye image would remain. Fischer himself did not find a way to stop the colour couplers and colour sensitizing dyes from wandering from one layer into the other, where they would produce unwanted colours.

Mannes and Godowsky followed that route, started experimenting with colour couplers, but their experiments were hindered by a lack of money, supplies and facilities. In 1922 Robert Wood, a friend of Mannes, wrote a letter to Kodak’s chief scientist Mees, introducing Mannes and Godowksy and their experiments, and asking if Mees could let them use the Kodak facilities for a few days. Mees offered to help, and after meeting with Mannes and Godowsky agreed to supply them with multi-layer emulsions made to Mannes and Godowsky’s specifications. Financial aid, in the form of a $20,000 loan, was supplied by the investement firm Kuhn, Loeb and Company, who had Mannes and Godowsky’s experiments brought to their attention by a secretary working for that firm Mannes had acquainted.

By 1924 they were able to patent a two-colour process. The important part of that patented process was a process called controlled diffusion. By timing how long it took for an image to form in the top layer, but not yet in the next layer beneath that one, they began to solve the problem that Fischer could not. Using this time-controlled way of processing one layer at a time, they could create the dye image of the required colour in only that layer in which it is required. Some three years later they were still experimenting using this controlled diffusion method of separating the colours in the multi-layer emulsion, but by then they had decided that instead of incorporating the colour couplers into the emulsion layers themselves, they could be added to the developing chemicals, solving the problem of wandering colour couplers. The only part left of Fischer’s original problem with a multi-layer emulsion were the wandering sensitizing dyes.

In 1929 money ran out, and Mees decided to help them once more. Mees knew that the solution to the problem of the wandering dyes had already been found by one of Kodak’s own scientists, Leslie Brooker. So he gave Mannes and Godowsky enough money to pay off the loan Kuhn Loeb had supplied and offered them a yearly salary. He also gave them a three-year deadline to come up with a finished and commercially viable product.

Not long before the three-year period would expire, at the end of 1933, Mannes and Godowsky still had not managed to come up with anything usable, and thought their experiments would be terminated by Kodak. Their only chance for survival was to invent something in a hurry. Something that the company could put into production and capitalise. Mees however granted them a one year extension, and still not having solved all the technical challenges they had to solve, they eventually presented Mees with a two-colour movie process in 1934. Two-colour, it must be noted, as was the original Kodachrome invented by John Capstaff some 20 years earlier.

Mees immediately set things in motion to produce and market this film, but just before Kodak was about to introduce the two-colour film in 1935, Mannes and Godowsky completed work on the long awaited but no longer expected, much better, three colour version. On April 15, 1935, this new film, borrowing the name from Capstaff’s process, was formally announced.

It was first sold in 1935 as 16 mm movie film and the following year it was made available in 8 mm movie film, and in 35mm and 828 formats for stills cameras.In later years, Kodachrome was produced in a wide variety of film formats including 120 and 4×5, and in ISO/ASA values ranging from 8 to 200.

————————-

Kodachrome films are non-substantive. Unlike substantive transparency and negative color films, Kodachrome films did not incorporate dye couplers into the emulsion layers. The dye couplers were added during processing.[17] This means that Kodachrome emulsion layers are thinner and less light is scattered upon exposure, meaning that the film could record an image with more sharpness than substantive films.[18] Transparencies made with non-substantive films have an easily-visible relief image on the emulsion side of the film.[19] Kodachrome films have a dynamic range of around 12 stops, or 3.6–3.8D

The color rendering of Kodachrome films was unique in color photography for several decades after its introduction in the 1930s.[21] Even after the introduction of other successful professional color films, such as Fuji Velvia, some professionals continued to prefer Kodachrome, and maintain that it still has certain advantages over digital. Steve McCurry told Vanity Fair magazine:[22]

If you have good light and you’re at a fairly high shutter speed, it’s going to be a brilliant color photograph. It had a great color palette. It wasn’t too garish. Some films are like you’re on a drug or something. Velvia made everything so saturated and wildly over-the-top, too electric. Kodachrome had more poetry in it, a softness, an elegance. With digital photography, you gain many benefits [but] you have to put in post-production. [With Kodachrome,] you take it out of the box and the pictures are already brilliant.- Steve McCurry

David Friend (February 9, 2011). “The Last Roll of Kodachrome—Frame by Frame!”. Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

Kodachrome, and other non-substantive films, required complex processing that could not practicably be carried out by amateurs. The process underwent four significant alterations since its inception. The final version of the process, designated K-14, was introduced in 1974. The process was complex and exacting, requiring technicians with extensive chemistry training and large, complex machinery.

——————————–

The Kodachrome product range diminished progressively through the 1990s and 2000s.

- Kodachrome 64 film in 120 format was discontinued in 1996.[14]

- Kodachrome 25 was discontinued in 2002.

- Kodachrome 40 in the Super 8 movie format was discontinued in June 2005,[51] despite protests from filmmakers.[52] Kodak launched a replacement color reversal film in the Super 8 format, Ektachrome 64T, which uses the common E-6 processing chemistry.[53]

- Kodachrome 200 was discontinued in November 2006.

- Kodachrome 64 and Kodachrome 64 Professional 135 format were discontinued in June 2009

——————————————-

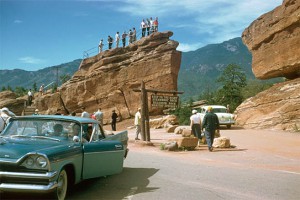

Kodachrome was the subject of Paul Simon‘s song “Kodachrome”, and Kodachrome Basin State Park in Utah was named after it, becoming the only park named for a brand of film.

source:

http://www.codex99.com/photography/77.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kodachrome