monmec

is marius parghel

verifica asta afara II

source: http://technologizer.com/2011/06/08/polaroid/

Polaroid’s SX-70: The Art and Science of the Nearly Impossible

A man, a company, and the most wildly ambitious consumer-electronics device of its era.

By Harry McCracken Wednesday, June 8, 2011 at 3:00 am

Polaroid co-founder Edwin Land with an SX-70 and an SX-70 snapshot in his Cambridge, Massachusetts office on November 1st, 1972. Photo: Joyce Dopkeen/Getty Images

What makes a gadget great? You might argue that it’s determined at least in part by how many lives the product in question touches. Back in 2005, when I helped choose a list of the fifty greatest gadgets of the past fifty years, we ranked the Sony Walkman as #1 and Apple’s iPod as #2. Fabulous gizmos both; I suspect, however, that they wouldn’t have topped the list if they hadn’t been bestsellers of epic proportions.

The SX-70–specifically, the SX-70 which I bought at an antique store in Redwood City, California in April of 2011.

But greatness isn’t a popularity contest–not primarily one, at least. Maybe it has more to do with the concept expressed by Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law: making technology indistinguishable from magic. By that measure, I can’t think of a greater gadget than the SX-70 Land Camera, the instant camera that Polaroid introduced in April 1972. We ranked the SX-70 eighth on that 2005 list, but the sheer magnitude of its ambition and innovation dwarfs the Walkman, iPod, and nearly every other consumer-electronics product you can name.

In 1972, instant photography was no longer a novelty: the world had been introduced to it in 1947 when Polaroid co-founder Edwin H. Land unveiled the Model 95, the company’s first camera. His invention–for decades to come, all Polaroid models would be officially known as “Land Cameras”–attracted enormous attention, and the company thrived as it introduced new, improved models throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

There’s a rule they don’t teach you at Harvard Business School. It is, if anything is worth doing it’s worth doing to excess.

–Edwin Land

The existence of previous instant cameras only helped emphasize what a great leap forward the SX-70 was. Unlike any previous Polaroid, it was a single-lens reflex (SLR) model with a viewfinder that showed exactly what you’d get. Unlike any previous Polaroid, it folded up into a 1″-thick leather-encased brick that was (just barely) pocketable. Unlike any previous Polaroid, it built the battery into the film pack. Even the flash–in the form of a Polaroid invention called a flashbar that packed ten bulbs into a double-sided array–was custom-designed for the SX-70.

Most important, unlike any other Polaroid, the SX-70 asked the photographer to do nothing more than focus, press the shutter, and pluck the snapshot as it emerged from the camera–and then watch it develop in daylight. It was the first camera to realize what Edwin Land said had been his dream all along: “absolute one-step photography.”

The cover of Polaroid’s SX-70 brochure didn’t demonstrate any false modesty.

“The virtual cascade of revolutions, mechanical, optical and electronic, that made the SX-70 possible,” rhapsodized a Polaroid brochure, “had only one purpose: to free you from everything cumbersome and tedious about picture-taking, so that it could become at last the simple creative act it should be.” Edwin Land himself reportedly said that the SX-70 incorporated 20,000 technological breakthroughs (we can forgive him if he estimated on the high side). No two estimates of the total cost of the project seem to be the same, but they’re all in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Longtime Polaroid executive Peter C. Wensberg captured the enormity of it all in his 1987 book Land’s Polaroid:

The camera was to include revolutionary optics and a complete set of photonic controls, some of which had not yet been invented. Three Polaroid factories were being built simultaneously: a negative plant in New Bedford, a film assembly plant in Waltham, and the new camera assembly plant in Norwood…Each required process machinery that was yet to be conceived, built, and installed by Polaroid engineers. Many of the most important manufacturing issues had not been solved, since the specifications of the camera and film were still changing.

The SX-70 program was so complex and so extended the boundaries of half a dozen technologies that those who worked on it had difficulty in stretching their faith and their optimism beyond the piece of the whole on which their own energies were concentrated. Land was virtually the only person in the company who knew in details all the difficulties that had to be surmounted. The rest of us could only guess.

“Don’t undertake a project,” an oft-quoted Land maxim goes, “unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible.” The SX-70 was both.

The story of the SX-70 isn’t one of unalloyed triumph–in fact, it’s rather bittersweet. Polaroid had talked about it being a game-changer on the same level as the telephone and television, but both the camera and the film suffered from technical problems at first, and didn’t meet initial sales projections. (Eventually, the company ironed out the glitches and profitably sold millions of cameras and film packs based on the SX-70′s innovations, especially after they migrated from the original $180 model into more affordable cameras such as 1977′s $39.95 OneStep.)

Just seven years after the SX-70′s national rollout, Polaroid’s board forced Land –the company’s co-founder, resident genius, and guiding spirit–to step down as CEO. And by the turn of the century, instant photography as Land had invented it was seemingly obsolete, leading Polaroid to declare bankruptcy (twice!) and discontinue the manufacturing of cameras and film.

None of this makes the SX-70 less amazing. As hyper-enthusiastic as initial press coverage of the camera was, it underestimated the scale of Polaroid’s accomplishment in some respects. The camera and film pushed the optics and chemistry available in the early 1970s so far that they remain remarkable even though today’s digital cameras outperform them in countless ways. And not one digital camera can match the SX-70′s principal feat: handing you a beautiful, sizable print of your photo the moment after you snap it.

SX-70 snapshots from The World of SX-70, a Polaroid instructional book.

I was nine years old in 1973, the first year the SX-70 received widespread distribution–far too young to have one of my own or even be entrusted with anyone else’s for very long, but not too young to be dazzled by it. A family friend owned one; I remember eyeing it enviously, but don’t recall whether he ever let me take a photo.

How to open the SX-70. From the camera’s manual.

The Polaroid camera of my youth was a $25 Super Shooter, which was introduced in 1975 and based on aging, pre-SX-70 technology. Using it required precise timing and dextrous handling of peel-apart film, and when I wasn’t careful, I got nasty developing chemicals on my hands. (Thirty-five years later, my fingertips can still feel the burning sensation.) I still had a blast with it, though.

Eventually, I owned and enjoyed Polaroids that were descendants of the SX-70, such as 1986′s Spectra. I can’t recall precisely when I stopped using them, but I do know that it was well before I got my first digital camera. That was well over a decade ago.

A few weeks ago, however, I was rummaging through stuff at an antique mall when I spotted a leather-wrapped box that looked intriguing and vaguely familiar. It took me a second or two to figure out what it was: an SX-70. Then I had to figure out how to unfold it, which I did by consulting a handy-dandy YouTube video on my iPhone.

As I tugged the camera open, it went from flat to spectacularly three-dimensional, like an ingenious pop-up book. I was dazzled all over again, and couldn’t resist buying it. And I wanted to learn more about my new plaything. I started by pinging my friend Phil Baker, since I knew he’d worked on the SX-70 as well as Apple’s Newton and first PowerBooks, the Think Outside Stowaway keyboard, Barnes & Noble’s Nooks, and other high-profile gizmos. The more I learned about the SX-70, the more fascinating I found it, which is why this article is…well, rather long for a blog post.

Two master demonstrators. Edwin Land shows the new Time Zero film at Polaroid’s 1979 annual meeting, in a photo from Alan R. Earls’ book Polaroid; Steve Jobs introduces the MacBook Air, in a snapshot that PCWorld’s Tim Moynihan took at Macworld Expo SF 2008.

Speaking of Phil Baker’s onetime employer Apple, the parallels between it and Land’s Polaroid are deep. Eerie, even. If the iPad had been a camera introduced in 1972 rather than a computing device introduced in 2010, it would have been the SX-70. When I read the following passage in Insisting on the Impossible, Victor K. McElheny’s excellent 1998 biography of Land, I immediately thought of Apple’s tablet:

Land intended Aladdin [the SX-70's code name] to terminate a succession of shortfalls and compromises and make photography more truly intuitive and impulsive by taking away manipulative barriers. To many amateur and professional photographers, who reveled in the variety and complexity of their equipment, Aladdin was no more welcome than earlier one-step systems. For the mass of photographers, however, instant photography was welcome. Time after time, they reached for the minimum of fuss that Aladdin represented.

…An artist by impulse, [Land] insisted that SX-70, like its predecessors, be absolutely new, unexpected, surprisingly useful, emotionally pleasing, and life-changing.

(I promise to drop this metaphor now, but if the SX-70 was an iPad, that means that earlier Land Cameras were Macintoshes, and non-instant cameras of the Kodak type were DOS PCs.)

Edwin Land was brilliant, prescient, prickly, and demanding, and hounded his employees into doing great things they might never have accomplished otherwise. That sounds like Steve Jobs. Land described photography as “the intersection of science and art.” Jobs likes to cite Land’s quote and says that Apple’s work sits “at the intersection of the liberal arts and technology,” a location which is surely in the same neighborhood. Land demoed new Polaroid products himself at corporate events that were famous for their hypnotic effect. Jobs carries on the tradition. And both Land and Jobs were forced out of the companies they founded, in two of the more preposterous decisions in business history.

I could go on: Polaroid’s advertising and packaging, for instance, emphasized classy minimalism. So do Apple’s.

It’s possible to overstate the similarities: Edwin Land, for instance, was profoundly involved in the engineering and chemistry of Polaroid products in a way that Jobs is not with Apple’s wares. Overall, though, Polaroid resembles Apple more than it did any of its 20th-century competitors. And Apple resembles Polaroid more than it does any 21st-century consumer electronics company.

I’ll continue to bring up Polaroid/Apple parallels throughout this article. Really, it’s impossible to avoid doing so.

The Man Behind the Camera

There’s probably an alternate universe out there in which Edwin Land didn’t invent instant photography and is still regarded as one of the great scientific visionaries of the 20th century. Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1909, he was in many ways the prototypical technologist/entrepreneur–a dreamer and doer who was endlessly dedicated to turning research and development into products with a shot at changing the world.

In 1936, Popular Science reported on Edwin Land’s (unrealized) dream of reducing highway carnage through use of polarized headlights. Polaroid didn’t yet exist under that name.

Land got his start in the same way Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg would decades later: by dropping out of an excellent college to focus on making stuff. In fact, he dropped out of Harvard as often as Gates and Zuck combined, having left in 1927, returned in 1929, and then quit again in 1932, one semester short of graduating. Later, he received honorary degrees from Harvard and many other institutions; to this day, Polaroid veterans call him “Dr. Land,” an honorific which only a heartless churl would begrudge him.

In Land’s case, the stuff that he left school to make was the first synthetic material capable of polarizing light, which he invented at the age of nineteen. In 1932, he and a Harvard instructor formed the Land-Wheelwright Laboratories to commercialize the technology; the company morphed into Polaroid in 1937. Eventually headquartered in Cambridge, Mass. in between Harvard and MIT, Polaroid advocated the use of polarized material in applications that didn’t pan out, such as car headlights. It pursued markets that took years to take off, including 3D movies. And it went after ones that were a success from the start, such as sunglasses and photographic filters. (The latter were marketed by Eastman Kodak, Polaroid’s first paying customer.)

Today, polarizers descended from Land’s first great invention are everywhere–for instance, they’re a key component in every LCD.

During World War II, Polaroid performed government work on projects such as reconnaissance photography, an effort which continued into the 1950s as Land became an adviser to President Dwight Eisenhower and spearheaded the design of cameras used in the U-2 spy plane and satellites. That was just a side job, though. By then, he had already created and commercialized the product with which he and Polaroid would become synonymous: the instant camera.

Edwin Land demonstrates his invention in 1947, as seen in LIFE magazine.

He always said that his creation had been prompted by a toddler’s innocent question. As he told LIFE in 1972:

One day when we were vacationing in Santa Fe in 1943 my daughter, Jennifer, who was then 3, asked me why she could not see the picture I had just taken of her. As I walked around that charming town, I undertook the task of solving the puzzle she had set for me. Within the hour the film, and the physical chemistry had become so clear that I hurried to the place where a friend was staying, to describe to him in detail a dry camera which would give a picture immediately after exposure…four years later, we demonstrated the working system to the Optical Society of America.

Polaroid’s Model 95 the first instant camera. Courtesy of Marc Rochkind of Basepath.com.

Land gave the project to build the world’s first instant camera the code name SX-70, indicating that it was his seventieth special experiment. (Polaroid would reuse that name a quarter-century later.)

The Boston Globe‘s George Green, who attended Land’s Optical Society demo, called it “the A-bomb of photography…revolutionary, spectacular, and amazing.” The Model 95 listed for $89.75 (about $800 in 2011 dollars) and took only sepia photos. It went on sale the day after Thanksgiving 1948 at Boston’s Jordan Marsh department store and was a sensation. Polaroid had hoped to sell fifty-six cameras by Christmas, but consumers snapped them all up the first day, along with all the film. When the camera rolled out nationally, it sold so briskly that the company was forced to ration them.

An early Polaroid ad.

Over the next two decades, Polaroid released an array of cameras. In 1963, it unveiled instant color film; in 1965, it introduced the Model 20 Swinger, its first truly inexpensive model at $19.95. Polaroid’s sweeping portfolio of patents–Land himself eventually received 533 of them, second only to Thomas Edison–ensured that no other company could manufacture instant cameras.

Land’s relationship to his company was as symbiotic as they come. Richard Wareham, a key contributor to the SX-70′s design who worked at Polaroid for 33 years, described the SX-70 project and Land’s unique role this way in a 1994 Optics & Photonics News special issue on Polaroid:

There was no managerial structure supervising the diverse groups involved. There were no written specifications that had to be accomplished. There was never any scheduled plan for when any task had to be completed. Yet one person, knowledgeable in every field involved, orchestrated this endeavor by challenging the available technology and the ingenuity of the many persons involved and expanding the boundaries of both. That person was Dr. Edwin H. Land.

Land wasn’t responsible for all of Polaroid’s bright ideas, of course. Quite the contrary: he assembled a dream team of gifted technologists, such as Howard Rogers, who largely invented color instant photography. Many of them stayed with the company for decades. But Land was a CEO with an intimate knowledge of optics and chemistry and other sciences that were essential to Polaroid products, as likely to contribute in the laboratory as the boardroom. And when he wasn’t inventing things himself, he was goading others to do so.

Edwin Land himself wasn’t crazy about budget-priced, mass-market Land Cameras such as 1965′s $19.95 Swinger. This example’s a bit yellowed with age.

He was not a mellow fellow. “[S]ome employees…find him difficult, overly demanding, and miserly in direct praise of subordinates.” wrote the Boston Globe‘s Robert Lezner in 1976. (He sounds like he’s describing Steve Jobs, who was 21 at the time and had cofounded Apple just a few months before.) Steve Herchen, who started at Polaroid in 1977, eventually became its VP of Research and Development, and is now Senior Vice President and Chief Technology Officer of Polaroid spinoff Zink Imaging, remembers that Land “would call you during Thanksgiving dinner if he had an idea for an experiment–and would expect you to come in.” But Herchen says the pursuit of experimentation and excellence at Land’s Polaroid was “contagious.”

“Everybody has something to say about Land, but very few people ever got to know him. He was the epitome of aloof,” says Paul Giambarba, who freelanced for the company from 1957 to 1983, creating Polaroid’s logo and famous color stripes, hundreds of packages, and other items that helped define its identity. “I liked [him] a lot, mostly because he didn’t meddle with what I did.”

Unseen SX-70 photos taken by Edwin Land–an enthusiastic amateur photographer himself–in 1979, probably with a test version of Time Zero, an improved SX-70 film. Courtesy of Tom Hughes.

“I think what is especially interesting about him is that he was both an insider and an outsider, a rebel and an establishment figure,” explains Alan R. Earls, the author of Polaroid. ”He attended Harvard but did not earn a degree. He was a tinkerer after the fashion of Edison but also was legitimately a scientist. He convinced people to spend a lot of money on instant photography, which probably had more novelty value than anything else. But at the other end of the spectrum he was an integral part of the military industrial complex–playing key roles in the development of US spy planes and satellites. And, of course, he was sort of a classic smart and sexy. He was very bright but also had tremendous personal presence.”

Before SX-70

By the 1960s, Land’s company became a celebrated American success. And yet instant photography wasn’t all that instant–and it certainly wasn’t brain-dead simple. You can tell that simply by reading old Polaroid manuals. Here, for instance, is everything you needed to know to get a picture out of the Model 250, a popular 1967 Polaroid, once you’d focused it:

The Model 250 and other pre-SX-70 Land Cameras could be great fun. I speak from recent experience: while I worked on this article, I picked up a 250 for cheap and used it to shoot photos around San Francisco. Still, it’s not hard to understand why Edwin Land craved something much, much better.

With their hulking physiques, fold-down lids, and lenses mounted on the front of telescoping cloth rigs that you pulled open like an accordion, the 250 and other Polaroids looked more like the sort of cameras Eastman Kodak had been building early in the century than they did the slick, consumery Kodak Instamatics of the 1960s. (Despite their moniker, the hugely popular Instamatics weren’t instant cameras–make what you will of the fact that Kodak introduced them in 1963, the year that Polaroid made a splash by bringing its first color film to market.)

The SX-70 with one of its immediate predecessors, the far bulkier, clunkier Model 440.

Pre-SX-70 Polaroids provided an infinite number of ways to botch a photo. “[I]f you don’t follow the instructions,” the manual for 1965′s Swinger jauntily warned, “you’re headed for plenty of picture taking trouble.” You had to hold the camera correctly. You had to pull out a tab, then pull out the film with the correct amount of force, neither too slowly nor too quickly. You had to time the development or risk ending up with a photo that was either underexposed or overexposed. It’s clear that Polaroid fretted over the complexity of its products: the SX-70′s predecessors were covered with labels that aimed to idiot-proof the process with instructions, warnings, and numbered steps.

And Polaroid photography was messy. After you pressed the shutter, you yanked a sandwich of photo paper, negative, and developing chemicals out of the camera. “You’d wait 60 seconds and peel it apart,” explains Zink’s Steve Herchen, “and in one hand you’d have a photo and in the other you’d have paper you’d throw away.” The photo was tacky to the touch and needed to dry for several minutes before it could be safely stacked with other pictures or stuck in a pocket. As for the paper, it was smeared with caustic jelly used to develop the picture. You had to avoid getting the jelly on your fingers, and figure out what to do with the goo-covered detritus.

Polaroid, a famously socially conscious company, was always embarrassed by the icky leftovers left behind by an instant photo. In the Model 250′s manual, it made a plea that sounded a little like it was addressing dog owners and beseeching them not to leave home without their pooper scoopers in hand:

Five years after the Model 250 was released, Polaroid announced the SX-70. Here’s what you needed to know to take a photo with it, once the scene was in focus:

A tad simpler, no? To slightly amend an early Kodak slogan, you pressed a button, and the SX-70 did the rest.

Project Aladdin

“Polaroid…has grown huge by creating products for which there was little detectable demand, until Edwin Land thought of them.”

–TIME

The SX-70 may have reached the market a quarter-century after the first Polaroids, but it was really the camera that Edwin Land had wanted to build all along. Bill McCune, who joined Polaroid in 1939 and eventually succeeded Land as president and then CEO, remembered him fantasizing shortly after work had begun on the first camera:

We were standing there …back in 1944, and he said “You know I can imagine a camera that is simple and easy to use. You simply look through the viewfinder and compose your picture and push the shutter release and out comes the finished dry photograph in full color.” Well, that was SX-70 but that was about 30 years later.

Development of a camera capable of absolute one-step photography began in earnest the mid-1960s, even though most of Polaroid’s employees didn’t know it at the time. “It was a decade-long effort when you include the chemistry and the film,” says Phil Baker, who ran Polaroid’s test lab at the time of the camera’s release. ”It was a secret project on the ninth floor at 565 Tech Square in Cambridge, and I never got a chance to look at it until the testing phase.” Even companies that provided parts were kept in the dark: in an article in IEEE Spectrum, Tekla S. Perry said that Texas Instruments, which provided circuitry for the exposure system, knew nothing about the camera that wasn’t absolutely mandatory to its work. Polaroid didn’t even inform TI that the SX-70 was an SLR.

An SX-70 patent drawing.

Polaroid could develop the camera in such a clandestine fashion in part because no outsider expected the company to build anything like it. As an uncredited TIME wrote in the magazine’s 1972 cover story:

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Polaroid is that it has grown huge by creating products for which there was little detectable demand, until Edwin Land thought of them. Each is, as Land says, sui generis—in a class by itself. That distinction makes conventional market research, in the words of one of his marketing executives, “a waste of time and money.” Polaroid did not spend a single dollar trying to discern in advance whether people would actually buy the SX-70.

Once again, Edwin Land’s Polaroid was the template for Steve Jobs’ Apple: in 2008, Jobs told Fortune that Apple does “no market research. We don’t hire consultants…We just want to make great products.”

“The idea of making a picture come out of the camera into the sunlight and have it develop in the sunlight is absolutely crazy. Who would have had the courage even to mention it to somebody, much less say they were going to do it?”

–Land associate William McCune

Like Jobs, Land also served as his company’s Nitpicker-in-Chief. “From one move to the next we found Edwin Land an acute observer,” wrote William Plummer, one of the key minds behind the SX-70′s optics, in the Optics & Photonics News special issue. “He was not only intensely conscious of the product as an object of commercial desire, to be formed and guided, but was also alert to small technical artifacts, subtle interactions between design and tooling.”

To emphasize the magical quality that Polaroid was aiming for, the absolute one-step photography project was known as Aladdin. But it was also given a code name that referenced the one that been given to Polaroid’s original instant camera back in the 1940s: SX-70. Land held off on giving the camera an official moniker until the last moment–at the annual meeting where it was unveiled in April of 1972, he said it might be called the American, and once suggested that it should be called the Nunc, after the Latin word for “now.” When TIME did a cover story on it in June 1972, it was still unnamed. But “SX-70″ stuck.

More photos from the The World of SX-70.

Dr. Land’s One-Man Show

The fullness of the SX-70 project may have been profoundly hush-hush, but Polaroid wasn’t above dropping clues that it had something big in the works. It started doing so at its annual meetings; for years, the company had been adding sizzle to those financial briefings by demoing products and previewing technologies.

At the 1969 annual meeting, Land mentioned a mysterious upcoming model which the Boston Globe dubbed “The Ultimate Camera” and said would be wallet-sized. Then in 1971, at a meeting held in the Norwood, Massachusetts factory that Polaroid was building to assemble the SX-70. Land talked about the camera in a manner meant to tantalize, not inform. He teased shareholders with a wooden prototype tucked into his pocket, claimed that it would become “the basic camera of the future,” and estimated it would sell for between $80 and $200.

Edwin Land demonstrates the SX-70 at Polaroid’s April 1972 annual meeting.

The SX-70′s real coming-out party took place at Polaroid’s next annual meeting, held on April 25th, 1972 at its four-acre warehouse in Needham, another Boston suburb. Land strode on stage before thousands of shareholders, Polaroid employees, reporters, and analysts. He lit his pipe. And then he began his presentation–which the New York Times described at the time as a “one-man show”–with these words: “Photography will never be the same after today.”

To demonstrate the SX-70′s sleek design, he plucked it from his inside jacket pocket with, as Popular Science‘s Arthur Fisher wrote, “the air of a magacian reaching for a very special rabbit.” Storing the camera in a pocket was itself an impressive trick: no previous Land Camera had been remotely pocketable. (The SX-70 was also far lighter than its ancestors–22 ounces versus two and a half pounds.)

Not that the SX-70 was that petite. “The rumor is that he had special suits made for the camera,” says Phil Baker, who was present that day. I can believe it: when I tried to replicate Land’s trick four decades later, I found the SX-70 so excruciatingly snug a fit that it threatened to do damage to my jacket’s seams.

Land unfolded the SX-70 and snapped five photos in less than ten seconds–a feat that would have been impossible with earlier Land Cameras, which required manual removal of the film and careful timing of its development. He said that the camera consisted of “three hundred resistors wrapped in top-grain leather.” He explained that the case consisted of brushed chromium bonded to a new polymer material–a fancy way of saying “chrome-plated plastic.” He said that the quality of the pictures’ color that was “astonishing, having qualities for which we have no names.”

After the presentation, attendees were invited to visit picture-taking stations, each with its own theme, such as a birthday party and a poker game. They weren’t permitted to snap photos themselves or even touch the camera and snapshots taken by demonstrators, but it was still spectacular.

The parallels of all this with Steve Jobs’ “Stevenote” unveilings of Apple products are remarkable. (Okay, except for the part about Land puffing a pipe onstage.) I don’t know of any evidence that Jobs modeled his launch events on the ones that Land conducted. But for decades now, Apple’s founder has used the same template as Polaroid’s co-founder: dramatic unveiling, feature walkthrough, lavish praise, individual demos. Jobs may have perfected the reality-distortion field, but Edwin Land invented it. And they may have been the only two CEOs in tech-company history who could pull it off.

As with Jobs and Apple products, the fact that Land was given to hyperbole didn’t mean that the device he was hyping wasn’t extraordinary. Polaroid commissioned filmmakers Charles and Ray Eames–better known for their modernist furniture designs–to produce a mini-documentary on the SX-70 as part of its marketing campaign. Thirty-nine years later, it remains an excellent explanation of the camera’s appeal and innovations. (Elmer Bernstein’s score adds an discordantly haunting flavor at times, though–and I’m unclear why distinguished astrophysicist Philip Morrison takes over the narration towards the end.)

So what had Land demonstrated at Polaroid’s annual meeting, exactly?

In its folded, boxy configuration, the SX-70 has been compared to a cigar case, a flask, and a portable cassette recorder–points of reference that probably had more resonance when a higher percentage of American households had cigar cases, flasks, and portable cassette recorders lying around. But the truth is that it doesn’t look all that much like anything else, period, in part because the top of the viewfinder–which doubles as the grip you use to pull the case open–gives the whole thing an eccentric double-decker feel.

The SX-70′s lavish use of leather is also striking. It’s a material rarely seen in consumer-electronics products of any era, for good reason: among other manufacturing challenges, it has a tendency to shrink in humid environments. But Land had insisted on it, and made the investments necessary to make it feasible–a move that Phil Baker compares to Apple’s use of aluminum.

Cutaway view of the SX-70 from the March 1973 issue of Popular Mechanics.

Once the camera is unfolded and ready to use, it still doesn’t look that much like a a camera. The industrial design was done by Henry Dreyfuss Associates, a famed firm that had been responsible for everything from locomotives to TIME magazine to the Princess phone. (Along with his terminally ill wife, Dreyfuss himself committed suicide in October 1972, after the SX-70′s announcement but before its release; his company continued to work with Polaroid on later cameras.)

As Julian Edgar has written, the unfolded SX-70 resembles “a model of an avant-garde tent, or a sculpture destined for a museum of modern art.” The viewfinder sits atop the camera like a lookout tower. The shutter button and focusing thumbwheel are on the front near the lens; photos emerge from a tray marked “POLAROID SX-70 LAND CAMERA.” The innards are protected by fabric walls.

The whole structure seems to hunch forward in a vaguely anthropomorphic fashion, as if it were impatient to get going; it has what an automobile writer would describe as an aggressive stance. If you hold the SX-70 level, as you would any other camera, the lens points down rather than straight ahead, a characteristic which led newbies to snap photos with oddly off-center compositions.

In October 1972, LIFE published this infographic showing how light traveled through the SX-70.

Aside from the shutter button, focus, and a wheel to adjust lightness/darkness, the SX-70 has no controls. Land’s notion was that freeing the photographer from complexity would permit him or her to concentrate on capturing a moment rather than photography.

Of course, freeing the photographer from complexity required plenty of complexity within the camera. The SX-70 is an SLR, but unlike any one that preceded it–for starters, other SLRs don’t fold up.

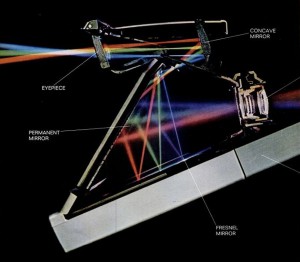

As you peer through the viewfinder, light rays enter the camera through the four-element lens and bounce off a fixed mirror at the back of the camera onto a hinged, ridged fresnel mirror that sits atop the film pack. The ridges in that mirror bundle the light up and shoot it back onto a different part of the fixed mirror, whereupon it caroms onto a small plastic concave mirror visible from the eyepiece.

When you push the shutter button, the fresnel mirror pops up, covering the fixed mirror–and revealing another mirror on the back of the fresnel. This one bounces the light onto the uppermost piece of film in the film pack, exposing it. Then a pick nudges that piece of film towards the motorized rollers. They grab it and propel it into the outside world with a distinctive whirring sound, initiating the development process along the way.

An SX-70 photo develops, as shown in a brochure for the camera.

As impressive a feat of engineering as the SX-70 was, an at least equal percentage of the system’s ingenuity went into the film. The New York Times‘s Robert Reinhold did a fine job of explaining the artful chemical choreography that was set in action when you pushed the shutter button:

A moment after the film is exposed through a thin four-element lens, the whole film card is ejected from the camera by a small motor powered by a flat six-volt battery that is packed with each set of 10 film cards. As a card leaves the camera, it passes between two tiny steel rollers that rupture a small “pod” containing a few drops of processing reagents, which are spread evenly between the negative lower layers of chemicals and the positive “image receiving” layer at the top.

This instantly starts the development process. The chief ingredients, an alkali (potassium hydroxide), and a white pigment (titanium dioxide), put down the dark curtain that prevents light from fogging the developing image. These special dyes were chosen because they have the unusual property of turning black in highly alkaline surroundings but clearing in acid.

Under this protective veil, the alkali quickly seeps down and dissolves the dye developers. The dyes that remain unoxidized, or uncaptured, are free to migrate forward through the various layers and appear on the image surface.

In a few minutes the correct amount of dye has been deposited on the image-receiving layer, and a built-in chemical timer helps to stop the dye movement and to clear the curtain.

While all the other reactions are proceeding, the alkali is slowly eating away a tough plastic barrier spacer. It takes several minutes.

Once it breaks through, the alkali hits a layer of acidic plastic, which promptly neutralizes the alkali.

This causes the curtain to turn clear, and at the same time other chemical actions are halted. Thus, the photograph is preserved.

The fact that SX-70 film put everything needed to create a photograph into the photograph didn’t just render the process more magical: it also made it tidier and more trouble-free. You didn’t have to deal with gunky paper or wait for the photo to dry. And each film pack included its own battery, so photographers didn’t need to worry about a separate battery that might conk out halfway through a pack.

Unlike earlier Land Cameras, the SX-70 produces almost perfectly square images–and at 3 1/8″ by 3 1/16″, they’re smaller than the rectangular snapshots from previous models. The chemical pod sits on the backside of the photo below the image, so the front side of the picture has a tall white border below the image–a unique characteristic of integral-film photos that makes them instantly identifiable to this day.

The elongated border below photos made using SX-70 film (and subsequent Polaroid integral formats) is there to make room for a chemical pod on the back, but it gives the pictures an unmistakable look and provides a handy space for annotations, as seen in these photos I bought at an antique store.

Other Land Cameras of the era used various types of disposable flashcubes, which held four flashes apiece. The SX-70 ditched cubes for a new type of flash designed especially for it: the flashbar. It contains ten flashes–neatly matching the ten photos in an SX-70 film pack–and is smart enough to determine which flashes are unused and to prevent you from trying to take a flash photo when all ten are spent. Polaroid helpfully suggested that SX-70 owners attend events such as parties with an SX-70 in one pocket and three film packs and three flashbars in another.

Hitting the Market

The annual meeting unveiling set off an ongoing extravaganza of press attention, LIFE, TIME, BusinessWeek, and Popular Science all eventually devoted cover stories to the camera. Coverage was breathless: among the words used to describe the camera were magic, unbelievable, impossible, and revolutionary.

The annual meeting unveiling set off an ongoing extravaganza of press attention, LIFE, TIME, BusinessWeek, and Popular Science all eventually devoted cover stories to the camera. Coverage was breathless: among the words used to describe the camera were magic, unbelievable, impossible, and revolutionary.

Polaroid’s April announcement had really been a pre-announcement. The company said it planned to have the camera out by Christmas 1972, at a price that turned out to be on the high end of its earlier estimate: $180 (about $950 in current dollars), with ten-packs of film going for $6.90. But in September, it was forced to delay the camera’s release, a decision it blamed on its inability to produce sufficient quantities of SX-70s quickly enough for the holiday season. In the end, the camera was released in late 1972 in a limited fashion in the Miami area–Polaroid loved Florida, because vacationers went there, took lots of snapshots, and then showed them to their friends–and the national rollout was postponed until the fall of 1973.

Paul Giambarba’s packaging for the SX-70 and related products. Photo courtesy of and copyright (c) Paul Giambarba.

The SX-70, its film, and accessories came in boxes created by Paul Giambarba. “When SX-70 came along, [Land] insisted on a white box,” Giambarba remembers. “There were the usual groans one might expect in a corporate environment, but I was very pleased to have a parameter in place that I could work with.” His final designs featured squares of the Polaroid color stripes he had created and the names of the products in News Gothic type–and nothing else.

Polaroid had long been a heavy TV advertiser, and it decided to promote an unprecedented invention like the SX-70 by striking an unprecedented endorsement deal. The camera’s spokesman was Laurence Olivier, universally regarded as the English language’s finest actor. It was his first and last advertising campaign.

Olivier shot the commercials in Paris and reportedly received $250,000 for them; his contract stipulated that they couldn’t be shown in England.

The SX-70 was so radically new that Polaroid saw explaining it to the world as an ongoing responsibility, not a one-time affair. Its annual report for 1973 came with a booklet, The SX-70 Experience, which featured snapshots taken by Land himself. His introductory letter didn’t recap the camera’s technical accomplishments or boast about its success to date. Instead, it said that it unlocked hitherto-undiscovered admirable qualities buried deep in the human psyche:

We could not have known and have only just learned–perhaps mostly from children from two to five–that a new kind of relationship between people in groups is brought into being by SX-70 when the members of a group are photographing and being photographed and sharing the photographs: it turns out that buried within all of us–God knows beneath how many pregenital and Freudian and Calvinistic strata–there is latent interest in each other; there is tenderness, curiosity, excitement, affection, companionability and humor; it turns out that in this cold world where man grows distant from man, and even lovers can reach each other only briefly, that we have a yen for and a primordial competence for a quiet good-humored delight in each other: we have a prehistoric tribal competence for a non-physical, non-emotional, non-sexual satisfaction in being partners in the lonely exploration of a once empty planet.

An early SX-70 ad, looking rather like the Apple ads of a few years later.

Whew. (That was all one sentence!) Whether or not you buy this assertion, it’s so deeply personal that it’s hard to dismiss it as mere puffery. Land didn’t just want to sell cameras; he wanted to change how human beings related to each other.

Wordy and self-serving though Land’s sentiment may have been, he was onto something. I think if he was around today, he’d understand the appeal of photo-sharing sites and apps such as Flickr and Instagram.

Note that he called the camera–or, more precisely, the system comprising of both camera and film–not “the SX-70,” but simply “SX-70,” as if it were a living creature rather than a mechanical device. It was an unusual turn of phrase at the time: Kodak referred to “the Instamatic,” not “Instamatic.” But in years to come, Apple would consistently use the same approach: Apple II, Macintosh, iPod, iPad.

Bugs in the System

A 1974 Polaroid with a slogan that captures the SX-70 spirit perfectly. (Image borrowed from Repolaroid.com.)

The SX-70 may have been remarkable, but it was far from flawless. Nobody had ever built anything like it. And Polaroid, which had outsourced most of the manufacturing of its products in the past to companies such as Kodak and Bell & Howell, wasn’t experienced at building things on its own. It struggled both with its own assembly lines and with components provided by third parties, such as the electronic shutter module which Texas Instruments stepped in to provide after a version manufactured by Fairchild Camera proved too complex and pricey

Then there were the batteries built into the film packs, which were manufactured by the maker of Ray-O-Vacs. By the time early packs of SX-70 film reached stores and were bought by consumers, the batteries were sometimes too weak to power the camera They also produced fumes that gave photos an unwanted blue tint, a glitch that Edwin Land discovered for himself with some of his vacation snapshots. Polaroid eventually solved both defects–by building and operating its own battery factory. But before it did, it had to take back hundreds of thousands of defective film packs.

Just as serious, it turned out that the camera had a fundamental usability flaw. You focused it by turning a thumbwheel located near the red shutter button on the front. Land had wanted SX-70 owners to peer into the viewfinder and see a blurry image come into focus, much as SX-70 photos emerged as they developed. But Phil Baker’s tests of the camera had shown that consumers had trouble focusing it–a problem that was doubly serious because focusing the camera also set the exposure for flash photos. “People would get sharp-enough pictures,” he explains, “but the exposure was all over the place.”

He estimates that focusing problems ruined 30 percent of photos. Nothing was done about it before the first SX-70s shipped, in part because the idea of confronting Edwin Land with evidence that the SX-70 was imperfect was so intimidating.

Drawings from the patent for Phil Baker’s focusing aid.

Baker came up with a fix, which involved adding a split circle to the viewfinder. As the photographer turned the focusing thumbwheel, the two halves slid back and forth: a perfect circle indicated a perfectly-focused photo. It made the SX-70 less elegant but more usable. Once Baker was able to present the concept to Land, “I spent the better part of a week working with him on the solution I came up with, and ideas he had,” he remembers. The feature was implemented on new SX-70s coming off the assembly line, and was available as a retrofitted update for the camera’s earliest adopters.

Land did insist on the focusing aid being located not in the middle of the frame but towards the bottom, where he hoped it would be less glaringly obvious. That led to a usability glitch of its own, says Baker: “Everybody would use it as an aiming device and take portraits with the head on the bottom of the screen.” On the plus side, Polaroid was able to eliminate the focusing aid in 1978, when it introduced the SX-70 Sonar OneStep, the first autofocus SLR.

Technical gremlins weren’t the only thing that bedeviled the SX-70. Press coverage, so giddy at first, turned sharply critical in some cases. Popular Photography, a magazine which normally didn’t give much ink to instant photography, devoted twelve pages to a cover package titled “Polaroid’s SX-70: Behind the Ballyhoo.” In roughly equal parts, it was devoted to awestruck examination of the camera’s technical innovations and complaints about its shortcomings. (PopPhoto griped about shutter lag and the lack of a tripod socket, and said that Kodak conventional film produced better images.) Consumer Reports pointed out multiple downsides, from focusing issues to the $180 pricetag.

“What’s six months’ [delay] in the course of a revolution?”

–Edwin Land

In January of 1974, Polaroid announced that it had sold 415,000 SX-70s in 1973–which might sound like an accomplishment except that it also disclosed that it had expected to move a million of them. (Some reports say it bandied around a goal of several million.) By the middle of the year, it had sold 700,000 units in twelve months. The company explained that manufacturing difficulties had left it struggling to keep up with demand; paradoxically, it also said that crippling inflation–which hit 11 percent in 1974–had left consumers hunkering down and avoiding investments like a $180 camera.

Land, as quoted by Newseeek in November of 1973, shrugged off the SX-70′s bumpy rollout: “What’s six months [delay] in the course of a revolution?” Wall Street wasn’t so blithe. The company’s stock price fell by ninety percent between the SX-70′s 1972 launch, when irrational exuberance over the camera had driven shares to new heights, and 1974. A July 1974 Newsweek story called Polaroid “a company saddled with declining profits and an uncertain future.”

Ansel Adams, in an SX-70 photograph taken by his close friend Edwin Land for the booklet The SX-70 Experience. Courtesy of Tom Hughes.

Consumers may not have bought SX-70s in the numbers that Polaroid had expected, but some pretty high-profile photographers were charmed by the thing. Ansel Adams, a close friend of Edwin Land and a longtime Polaroid enthusiast and consultant, called the camera “a fantastic achievement” and covered it in an updated version of his how-to book Polaroid Land Photography He not only praised it but used it, as did Chuck Close, Walker Evans, David Hockney, Robert Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, and other notables. Andy Warhol was also an SX-70 owner, although his favorite Polaroid was apparently the wacky-looking $19.95 Big Shot, which he used to snap portraits of celebs such as Farrah Fawcett.

Walker Evans, who began his photography career in the late 1920s and died in 1975, was wary of the SX-70 at first but ended up owning three of them. Jerry L. Thompson, his student, assistant, and friend, wrote about the photographer and the camera in his 1997 book The Last Years of Walker Evans:

Social events were also occasions for [Evans] to photograph. Almost as soon as he started using his SX-70 he began to make close portraits. He had brought a number back from his trip to England, and he made pictures of students when he traveled to lecture. The camera is well adapted to portraits. It focusses close, and the flash sits just above the lens–there is no separate viewfinder that a flash so close to the lens might block–so shadows resulting from the flash are small and narrow, serving merely to emphasize the lower contours of facial forms. Also, the color balance of the film yields pleasing skin colors (probably not by accident); they tend to be a little warm, making the faces appear healthy, full of blood and life. The illumination of the flash falls off quickly, typically yielding close-ups that show a strongly volumetric face whose margins begin to fade into the surrounding warm darkness.

Norman Locks’ “Persimmons, Glass of Milk,” 1977. Courtesy of the artist.

Photographer Norman Locks published an entire book of SX-70 work, Familiar Subjects, in 1978, but they were anything but the straightforward photos of people and signs that Evans snapped. Locks had discovered that he could create striking effects–reminiscent of Photoshop effects, years before Photoshop existed–by moving the pictures’ emulsion around with a stylus before it dried, fiddling with colors and adding new lines on top of the original image until it seemed to be either a photo that looked a little like a drawing or a drawing that looked a little like a photo.

Locks explains why the SX-70 and SX-70 manipulation appealed to him:

I began using the camera during my first major job out of graduate school in Yosemite [as director of the photography workshop at the Ansel Adams Gallery]. In 1974, a technician/representative showed up with two new SX-70s and thirty boxes of film. I had never seen or heard of the camera before, but the two of us shot thirty packs of film in two days and I was hooked. It was shocking, after six years of college art to be so attracted to the point and shoot, but it in fact satisfied everything that I needed at the time….The camera was magic to me. The way it came out blank greenish gray and allowed the me to watch the image appear, much as a print in the developer– only in the field. The sound that the camera made was unique and immediately identified the SX-70.

The SX-70 allowed, in the process of manipulation a process of strengthening (clarification of form) and editing (removing the unnecessary) until the image idea was closer to my intent. The process combined my interest in drawing and painting, current and historical, with photography. The camera was great with intimate close-up imagery (focusing to 10 inches) such as still lives (painting again), family imagery (I was young with a young family) and the process of hand working created an intimacy between myself and the image that was a rewarding learning experience.

When I began working with the SX-70 I was administrating workshops for Ansel and teaching and had little time for darkroom work. I kept working with the camera because the work was satisfying.

Polaroid addict Andy Warhol poses with the SX-70.

Polaroid manipulation of the sort Locks practiced became an artistic genre that continues to this day; it also provided the cover art for a 1980 Peter Gabriel album.

(Locks’ editor, incidentally, was the late Andrew Fluegelman, who explains in the book’s foreword that he was also an SX-70 enthusiast. I was tickled to learn of his interest in the camera: he later became the founding editor of PC World magazine, a job I eventually inherited. He was also the first editor of Macworld and the inventor of shareware.)

Sons of SX-70

Soon after the SX-70 received widespread distribution in 1973, Polaroid began to release variants, aiming both to improve the technology and bring it to potential customers who would never plunk down $180 for an instant camera. 1974′s $149.95 SX-70 Model 2, for instance, a case made of white plastic and black vinyl rather than chrome and top-grain leather, a concession to economic reality that I can’t imagine Edwin Land being happy about. It was succeeded by 1975′s $99.95 SX-70 Model 3 , which folded up but wasn’t an SLR.

The OneStep–today, maybe the most immediately recognizable Polaroid of them all.

The SX-70′s most famous offspring–and an iconic American gizmo in its own right–was 1977′s Model 1000 OneStep. Built on SX-70 technology and using the same film, it listed for $39.95 (the equivalent of about $140 today), less than one-quarter of the original camera’s price. The SX-70 DNA was obvious, but so were signs of cost-cutting and a general desire to produce a piece of mass merchandise rather than a futuristic wonder. The OneStep didn’t fold, wasn’t an SLR, and used a fixed-focus lens, forcing photographers to stand at least four feet back from their subjects. Rather than being “wrapped in top-grain leather,” it was cheerfully plasticky, with a rainbow-stripe decal on its front. But it was, indeed, a one-step camera: you pushed a button, and the photo whirred out and developed before you.

Oh, and rather than hiring Sir Laurence Olivier and having him speak of the SX-70 in much the same rarified manner that Orson Welles used when praising Paul Masson wine, Polaroid signed up James Garner and an unknown named Mariette Hartley for commercials that became a pop-culture phenomenon in themselves (the duo also did ads for other SX-70 variants):

Elegant and understated the OneStep was not. It’s said that Land disliked it. But it was the smash that the original SX-70 never was, the best-selling camera of any type during the 1977 holiday season. Polaroid said that even round-the-clock production couldn’t keep up with demand.

Popular Science features the Kodak EK6–its most SX-70-like camera–on the cover.

Sales were brisk even though the OneStep faced a challenge that the first SX-70 hadn’t had back in 1972 and 1973: competition. In April of 1976, Eastman Kodak introduced its first instant cameras, the product of a crash program to enter the market spurred in part by fear that the SX-70 might indeed define the future of photography. (The company had the heebie jeebies about the camera as early as 1968, when Land showed Kodak executives test prints made using a very rough draft of the technology.)

For years, Polaroid and Kodak had been frenemies, both collaborating and competing. Kodak, which had been Polaroid’s first paying customer, also manufactured the negatives for pre-SX-70 Polaroid cameras, at the same time that instant cameras and Instamatics duked it out in the market. Its entry into the market that Polaroid invented terminated the companies’ peaceable relationship.

Kodak was a far larger company than Polaroid, with massive resources at its disposal, but it lacked one unique Polaroid asset: Edwin H. Land himself. That helps explain why it never attempted to create and manufacture anything like the SX-70 before Land did. But even after the SX-70 existed, Kodak failed to produce instant cameras with anything like its technical derring-do and design panache. By all accounts, its Kodamatics produced respectable pictures. They were ungainly and unappealing, though, and heavy–they weighed nearly twice as much as a comparable Polaroid.

I remember being off-put, at age thirteen, by the willful clunkiness of “The Handle,” a hand-cranked instant Kodak that made you perform manual labor to get the photos that cameras based on SX-70 technology delivered to you automatically:

Polaroid vs. Kodak

Kodak thought it had poured enough of its own research into its instant cameras to penetrate what eventual Land biographer Victor McElheny called Polaroid’s “wall of patents” in the New York Times. Polaroid begged to differ. Six days after Kodak announced its first instant cameras, Polaroid sued, saying that its competitor had violated ten of its patents. By then, Kodak had already sued Polaroid on antitrust grounds in Canada.

Kodak’s 1982 Pleaser 2–a downright goofy-looking camera–meets the SX-70.

The good news for Polaroid was that even with Kodak in the instant-camera business and advertising its products aggressively, Polaroid retained two-thirds of the market. The bad news was that it had lost one-third of an industry that it had invented, patented to a fare-thee-well, and believed was its alone.

It took five years until Polaroid’s suit against Kodak came to trial. Another four years elapsed until there was a verdict, which found that Kodak had violated seven Polaroid patents. The company was forced to discontinue its instant cameras. Continuing to make film for the cameras it had already sold was also forbidden, rendering them instant doorsteps. (It had to offer cash and coupons to consumers who’d bought the cameras.) And after years of additional legal wrangling, it ended up paying $925 million in damages and interest to Polaroid in July of 1991–a decade and a half after the case had begun, and four months after Land’s death.

We know that we’ll never be able to catch up with ourselves, so we won’t ever have to worry about others catching up.

–Edwin Land

Edwin Land was no patent troll. He “believed in patents as a protection for the small fish among the big fish,” says Victor McElheny in Insisting on the Impossible. Polaroid was a far smaller fish than Eastman Kodak, and its patents protected ideas which were indeed its own.

With the benefit of a few decades of hindsight, though, the legal victory against Kodak looks profoundly hollow. For one thing, the monopoly that Polaroid recaptured was already faltering. Instant camera sales peaked in 1978–when both Polaroid and Kodak were in the game and doing well–at 13 million units. By 1990, after Kodak had been ousted from the market, sales had fallen by almost two-thirds, to 4.5 million units. In other words, Polaroid sold more cameras when faced with competition from Kodak than it did when instant photography was its alone. And no product that it released after that was able to reverse the decline.

A Polaroid that had to deal with Kodak as a permanent rival might have worked harder to push instant photography far beyond the SX-70′s innovations. It would have had a stronger incentive to invent the next big thing–which in this case would have been consumerized digital photography. “No competition means you don’t the motivation within the organization,” notes Phil Baker. ”They were on a branch of technology that wasn’t going anywhere. They’d have to climb back to the trunk and find another branch.”

It’s true, however, that Polaroid had always been a company driven more by inward-looking ambitions than external forces. “We know that we’ll never be able to catch up with ourselves,” Newsweek quoted Land as saying at the SX-70′s introduction, “so we won’t ever have to worry about others catching up.” Even at the time, the magazine noted that he sounded a mite smug.

The Polavision Misadventure

Edwin Land demonstrates the Polavision system on April 26th, 1977. Copyright © Bettmann/CORBIS

Polaroid had announced the OneStep at its 1977 annual meeting, five years and one day after the one that it used to launch the SX-70. But the camera wasn’t the meeting’s big news. Land didn’t even demo it himself; he let his successor as Polaroid’s president, Bill McCune, do the honors.

The day’s big splash came when Land introduced Polavision, the first instant-photography system that produced motion pictures rather than still images. The level of hoopla may have exceeded the SX-70′s unveiling: Land began the meeting by calling Polavision “a new science, a new art, and a new industry,” and the demo included a gaggle of clowns, mimes, and dancing girls.

The Polavision system–camera, viewer, and film cartridge.

Land, who turned 68 a couple of weeks after the Polavision announcement, apparently believed in the new technology as passionately as he had in the SX-70. “I don’t know if he saw Polavision as his last hurrah,” says Tom Hughes, who was Polaroid’s Senior Art Director at the time. “but research and marketing resources were funneled into the project.”

The Polavision kit included a camera, instant-film movie cartridges, and a table-top viewing screen that doubled as a developer. It sold for $675–close to $2500 in 2011 dollars–and produced silent films that were two minutes and forty seconds long. It might have been a marvel if it had been introduced a decade earlier. Unlike the original SX-70, however, it had competition: video recorders and cameras which provided audio capability and far longer running times.

Polaroid may have given its movie system an SX-70-like unveiling, but the response was more skeptical this time. TIME‘s story on the announcement quoted one unnamed analyst: “This is a product that has much more scientific and esthetic appeal than commercial significance.”

Even within Polaroid, there were doubts. “We had a long series of discussions about Polavision,” Land’s longtime associate and successor Bill McCune told the Boston Globe after Land’s death. Land “was usually so perceptive, but in this case he simply didn’t want to face it. He was at a stage when he was much more difficult to talk to and he didn’t want to listen. [Polavision] became a personal thing. There was no way of stopping him.”

Polavision rolled out with ads featuring Danny Kaye, a spokesman of Olivier-like stature, expressing his wonderment:

But by 1979, the company responded to disappointing sales by paying Ed McMahon to pitch Polavision on The Tonight Show as a mundane business tool:

Marketing and sales blunders rather than technological ones hurt Polavision, insisted Land, who pointed out that video cameras and VCRs were far bulkier and pricier than Polaroid’s product. They were. But many industry watchers still saw even then that video was the future. So, apparently, did consumers, who avoided Polavision in droves: Insisting on the Impossible reports that Polaroid may have manufactured 200,000 systems and sold only 60,000.

Land continued to try to jump-start Polavision–McElheny says that he investigated partnering with Electro-Lux to sell systems door-to-door, like vacuum cleaners. He also demoed movies with sound at Polaroid’s 1979 annual meeting. Unlike the SX-70, however, Polavision never got past the first-generation version. For once, reality had trumped Edwin Land’s dreams.

Land After Polaroid

Polaroid wrote off $68 million on the Polavision mess in 1979. The next year, its board did something that’s still difficult to comprehend. As a reaction to Polavision and a general feeling that Land was increasingly obstinate and difficult to work with, it forced him to step down as CEO of the company he founded. In 1982–only a decade after the SX-70′s debut–he resigned his position as as chairman, left its board, and stated his intention to end all ties with Polaroid. (On the same day, the company reported a 72.6 percent drop in profits, due in part to a writeoff on equipment used to produce SX-70 film.)

Land sold all his Polaroid stock and turned his attention to the Rowland Institute for Science, a research center he founded, which continues its work today as part of Land’s alma mater, Harvard University. Relieved of the need to run a commercial business, he poured his energies into pure science, focusing on research relating to color vision.

In January of 1985, the BBC broadcast an episode of its Horizons program on color perception. Much of it was devoted to Land discussing his experiments in his own words–and there was even some vintage newsreel footage of him showing off the first Polaroid camera.

Here’s an excerpt:

Tom Hughes gave Steve Jobs a print of this photo by Naomi Savage, Man Ray’s niece, of Edwin Land at the Rowland Institute.

On the same day that the BBC shot footage at Land’s office for its show, he greeted another visitor: Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. The meeting was arranged by Tom Hughes, who had left Polaroid to work for Apple as design director on a new computer called the Macintosh. (He made the move in part because he was melancholy that he’d missed out on the birth of the SX-70–having started at Polaroid in 1976–and saw the same “magical” potential in the Mac.)

On an Apple business trip to Boston, Hughes recalls, he and Jobs “were talking about Polaroid and I learned that Dr. Land and Steve had never met. I called Dr. Land and he said ‘Come on over.’ It was 6 or 6:30 at night.” Jobs, Hughes, and another Apple employee named Kathryn Kilcoyne crossed a Charles River bridge by foot to get to Land’s office in Cambridge. Apple CEO John Sculley, who joined them there later, spoke about the visit in an interview with Leander Kahney.

Land showed his guests some of the same color experiments he’d presented to the BBC, as well as photos from his collection. And he bonded with Steve Jobs, whose then-new Macintosh showed SX-70-like ambition. ”It was like a father-son meeting between the two,” says Hughes, who remembers them “discussing the lifecycle of products from inspiration to development through to production.”

Hughes, who’d had the rare privilege of working at Land-era Polaroid and Jobs-era Apple, says he sees much of Land in Apple’s co-founder: “I feel Steve was very much influenced by him.”

Jobs would be honored by the comparison. In an interview published in the February 1985 issue of Playboy, he shared his thoughts about “brilliant troublemaker” Land and expresses astonishment at his removal from the company he founded:

You know, Dr. Edwin Land was a troublemaker. He dropped out of Harvard and founded Polaroid. Not only was he one of the great inventors of our time but, more important, he saw the intersection of art and science and business and built an organization to reflect that. Polaroid did that for some years, but eventually Dr. Land, one of those brilliant troublemakers, was asked to leave his own company—which is one of the dumbest things I’ve ever heard of. So Land, at 75, went off to spend the remainder of his life doing pure science, trying to crack the code of color vision. The man is a national treasure. I don’t understand why people like that can’t be held up as models: This is the most incredible thing to be—not an astronaut, not a football player—but this.

Five months or so after the Playboy interview was published, John Sculley pushed Jobs out of his position as head of the Macintosh team; Jobs resigned from Apple in September.

Edwin Land refused to attend an event celebrating Polaroid’s fiftieth anniversary in 1987. He continued his research at the Rowland Institute until his death 0n March 1st, 1991.

Polaroid After Land

Squeezing Land out of the company he created and exemplified apparently seemed like a good idea at the time. The void he left was, of course, unfillable. Polaroid didn’t claim otherwise. “Dr. Land is a genius, and much of the creativity of the company came from his perceptions and convictions about things,” William McCune, Land’s successor as Polaroid CEO, told the New York Times in 1983, a year after Land resigned as chairman. ”We obviously do not have a genius of that caliber in the company anymore.”

1998′s PopShots, a one-time-use instant camera. It was among Polaroid’s last-gasp attempts to reinvigorate interest in instant photography.

It also didn’t have a breakthrough of the caliber of the SX-70. The company continued to refine instant photography, introduce improved cameras and film, and enter new markets. But no new Land Camera did to the SX-70 what the SX-70 did to Land Cameras before it. (Actually, in a small but meaningful sign of disrespect for its founder and its history, Polaroid eventually stopped calling its products “Land Cameras.”)

In 2011, it’s tempting to misremember history and think that instant photography thrived until digital cameras started to become mainstream hits around the turn of the century. Not so. Starting in the 1980s, the SX-70 and its successors faced stiff competition from 35mm point-and-shoot cameras, which kept getting cheaper and more capable. One-hour film processing gave shooters semi-instant gratification: even if you didn’t own a Polaroid, it was possible to see your vacation photos while you were still on vacation.

The Polaroid camera was not a lifetime acquisition, but an evolving idea, an ongoing adventure, an exploration of technology.

–Peter C. Wensberg

For the first three decades of instant photography, some of Polaroid’s best customers had always been people who already owned Polaroid cameras. Peter C. Wensberg explained it in Land’s Polaroid:

Land…was teaching the American public, and by extension a world market, that the Polaroid camera was not a lifetime acquisition, but an evolving idea, an ongoing adventure, an exploration of technology. If that sounded like an improbable marketing plan, it had proved itself since 1950…yard sales were invented to get rid of old Polaroid cameras.

Unlike the SX-70, most Polaroid cameras of the 1980s and 1990s were short on features that would prompt consumers who already owned a perfectly good instant camera to buy a new one.

A 1990 Polaroid patent for a digital camera with a detachable printer.

Polaroid also managed to figure out early on that digital imaging would be important without benefiting much from that insight. According to a 2000 article in Strategic Management Journal by Mary Tripsas and Giovanni Gavetti, the company had created an electronic imaging group in 1981 and was spending 42 percent of its research and development budget on digital imaging by 1989. But it tended to think that consumers would want instant prints of their photos, and therefore focused much of its attention on printing rather than purely electronic photography. That was an understandable misjudgment considering that it made most of its profits from selling film, not cameras.

Like many companies started by brilliant people, Polaroid had suffered from founderitis.

–Alan R. Earls

“We have studied the needs of our customers in each market segment and those needs are driving the development of our new products,” Tripsas and Gavetti quote I. MacAllister Booth, Polaroid’s CEO from 1985 to 1995 (and a longtime Land lieutenant) as writing in the company’s 1989 letter to shareholders. That was the strategy that nearly every major corporation in America followed. But it couldn’t have been more different from the days when Polaroid’s product road maps was determined by Edwin Land’s instincts, not market research. It would never have resulted in a product like the SX-70, and it didn’t prepare the company for the future.

“I don’t think its failure was inevitable but like many companies started by brilliant people, Polaroid had suffered from founderitis,” says Polaroid author Alan R. Earls. “Land was the company’s greatest asset and greatest liability…Just as [makers of] minicomputers were blindsided by the advent of the PC and couldn’t adapt quickly enough, Polaroid, aside from any other problems it had, was badly hurt by the rapid emergence of digital photography. I’m sure with some luck and great management, things could have been different. But it would have been challenging.”

The Fall and Rise of Instant Photography

In this century, much of the news about Polaroid has been unfortunate, strange, or both unfortunate and strange. In 2001, it went bankrupt, its stock having fallen from almost $50 a share to 28 cents in three years. In 2002, a company called the Petters Group began licensing Polaroid’s once-mighty name for use on generic products such as TVs and DVD players; it then bought out Polaroid itself in 2003 for $426 million. In 2008, the Petters Group’s founder, Tom Petters, was arrested and charged with running a massive Ponzi scheme–he was later sentenced to fifty years in prison–and Polaroid went bankrupt again and ended up being sold once more.

A box of SX-70 film from Polaroid’s last year of production, 2006–complete with a sticker warning consumers that it was being discontinued.

2008 was also the year when the company stopped being Polaroid in any meaningful way, when it announced in February that it was ceasing production of instant film. The news thrust the company into the headlines in a way that hadn’t happened since the 1970s, but it shouldn’t have surprised anyone who was paying attention, since it had quietly stopped manufacturing instant cameras the year before that. (By then, it had been marketing consumer digital camera for years, but they were me-too products at best.)

Nobody except extremely loyal SX-70 owners and artists who liked to manipulate photos had noticed when the company quit making SX-70-compatible film in 2006. Anyone still shooting with a camera that required it at that point was using an antique: the last models in the line had come out in the 1980s.

Polaroid’s end of production didn’t mark the end of interest in Polaroid photography. Actually, it helped jump-start its rebirth. What had been an unwanted commodity suddenly looked like a precious resource.

Predictably, some folks hoarded unused film, either because they wanted to use it themselves or rightly figured out that there would be a thriving market on eBay for years to come. Hipsters became smitten with instant photography: When retailer Urban Outfitters offered some of Polaroid’s last cameras in 2009, they were gone within hours. And there are a bevy of Flickr groups devoted to sharing newly-taken Polaroids.

It’s possible to use Polaroid film long after its expiration date has come and gone. But the chemicals that perform the magic slowly degrade: you might get a faded picture or no picture at all, or find the film pack squirting gunk inside your camera. The only way that the SX-70 and later models could avoid the sad fate of Kodak’s instant cameras was if someone began making film for them again.

Impossible Project film, in boxes reminiscent of Paul Giambarba’s original Polaroid packaging.

That someone turned out to be Florian Kaps, an Austrian businessman and Land Camera admirer who operated a site called Polanoid.net. Within months of Polaroid’s announcement that it was ending production, he launched a quixotic crusade to save instant photography, appropriately dubbing it the Impossible Project.

In surprisingly little time, Kaps and and the team of Polaroid addicts and ex-employees he assembled started making progress. In October 2008 they bought the film-manufacturing equipment from a decommissioned Polaroid plant in Enschede, the Netherlands. They then consolidated it in one building and set about reviving production.

Owning Polaroid machinery without having access to the original ingredients that Polaroid used to make film turns out to be a little like owning a Polaroid camera but no film–it’s a good beginning, but only a beginning. With Polaroid’s original dyes and other materials unavailable, the Impossible Project had to start from scratch. It announced its first film in March 2010.

A photo I took on April 30, 2011 using my SX-70 and Impossible Project film. Using an unserviced forty-year-old camera with “experimental” film doesn’t make for the best results–but it still recaptures some of the original Polaroid magic.

The word the organization uses to describe its current films–color and black-and-white versions for both SX-70 cameras and their successors, the 600 series–is “experimental.” That’s about right. It’s overly sensitive: rather than getting to watch your photo develop, you need to immediately shield it from the light. The film sometimes sticks inside the camera rather than emerging when you press the shutter. And it may continue developing in unexpected ways after original Polaroid film would have settled down.

Most important, the Impossible Project is still working on the quality of the film, which produces pictures with an inconsistent, sometimes less-than-realistic look, akin to the effect intentionally sought by enthusiasts of the photographic pursuit known as Lomography, which uses cheap, toy-like cameras built in Russia and elsewhere.

“For what I do, the colors aren’t quite there yet,” says Polaroid photographer Grant Hamilton, who’s working on a documentary about the Impossible Project called Time Zero, which he hopes to release later this year. “But I’m patient. I’m completely blown away.” I’ve blown through several packs of Impossible Project film in my antique-store SX-70; the photos I’ve gotten have had a decidedly experimental look to them, but I’ve still enjoyed the experience of being, at long last, an SX-70 photographer. (For some much far impressive examples of Impossible Project photography than mine, check out the Impossible Project Flickr group.)

Right now, Impossible Project film has a lot in common with the test films that Polaroid futzed with in labs before it had anything that was ready to sell to millions of consumers. Kaps and his collaborators won’t have fully realized their impossible dream until their film is as good in its own way as the film Polaroid began selling in 1972. But they’ve already come far closer than anyone would have predicted a few years ago, and I wouldn’t bet against them. (The growing Impossible Project empire now includes retail outlets in Enschede, New York, Tokyo, and Vienna, each a temple to absolute one-step photography.)

Lady Gaga demonstrates new Polaroid products at CES 2011. A 1970s Edwin Land annual meeting this isn’t.